Homeward Bound: Returning to Vietnam

By Brad & Julie Davis

An Operation Babylift Vietnamese adoptee visits Vietnam.

I

wasn't sure what to feel as the flight attendant announced we were beginning

our descent into Saigon. It had been more than 20 hours since we began this

adventure, but it felt more like 20 years. In reality, though, my journey in

Vietnam began a long time ago. The anticipation of a long overdue homecoming

was about to come to life.

I

wasn't sure what to feel as the flight attendant announced we were beginning

our descent into Saigon. It had been more than 20 hours since we began this

adventure, but it felt more like 20 years. In reality, though, my journey in

Vietnam began a long time ago. The anticipation of a long overdue homecoming

was about to come to life.

My story in Vietnam began in a small orphanage in the central coastal city of Quy Nhon. During the Vietnam War, children were evacuated from the Ghenh Rang Orphanage during the North Vietnamese occupation, migrated south to Saigon, and eventually put on planes as part of Operation Babylift in 1975. Though there were many tragic outcomes as a result of the airlifts, they were a lifeline for several children, including me. I was one of the lucky ones. An adoption agency in the United States was eagerly anticipating my arrival, as was a family in Seattle that had just received news that a healthy one-year old girl was on the way.

During the years following my adoption, I was integrated into my new family and what little I may have experienced in Vietnam dissolved as my American life took shape. Just as my adopted family embraced me, I embraced American culture. Other than my physical appearance, I didn't symbolize Vietnam in any fashion. I relinquished all but my Vietnamese sir name, established American citizenship and shed everything else that resembled Vietnam.

For the duration of my adolescence, I felt completely disjointed from my Vietnamese heritage. I grew up feeling little to no association with Vietnam. Adopted as an infant and surrounded by mostly Caucasian friends, I knew little else and had no interest to understand what it was like to be Vietnamese. Though my family supported and encouraged Vietnamese influence in my life, I did not want to be different. I was determined to mold myself into any other form but Asian. I was never bothered by my inability to explain who I was and where I came from. In my mind, Vietnam was just a far away country tainted by the history of an infamous war, bearing no reflection on me as a person.

What little I knew about the War was bad and I felt people would dislike or reject someone that reminded them of such a painful period in our history. I held onto this burden for the duration of my young life, but as time went on, I realized the questions would forever follow me and intensify as I got older. Eventually, the distance I considered my refuge was replaced by the desire to absorb all that I could about Vietnam. These emotions were as foreign to me as the country itself. The disconnection that was once my safety net had transformed into a coming-of-age and I felt the need to finally come to terms with who I was.

It would take several more years before I could fully admit out loud what I already knew, but once I faced the inevitable, understanding and consuming Vietnam became my passion. I finally identified the need and desire to co-exist as both Vietnamese and American. Years of mixed emotions were colliding and all that I had kept submerged was about to be tested as I embarked on a two-week journey to the country where it all began. My best friend and husband, Brad, was fundamental in helping me reach this point in my life, and he sat beside me as our plane descended into Saigon.

Much to our surprise, we established our bearings quite easily in the city. We were overwhelmed with the sites, smells and sounds only native to Vietnam. It was exhilarating. The streets were crammed with bustling bodies and motor scooters. Silk storefronts, beautiful Vietnamese Ao Dai dresses and lacquerware shops dotted the trendy Dong Khoi District. It was vibrant, alive and it felt good. I was eager to consume it all.

After

a brief city tour, including the Reunification Palace, the Cho Lon Market, Notre

Dam Cathedral and the War Remnants Museum, we set off on a two-day side trip

south to the Mekong Delta, otherwise known as the rice basket of Vietnam. Navigating

Highway 1 at speeds exceeding 110 mph with our guide, Ut, we headed towards

the Delta, the floating markets and the city of Can Tho. As we set out for the

morning market on the Delta, we passed through narrow canals shaped by dilapidated

homes flushed up against the banks. The Kodak moments - a woman rinsing clothes

in the river, a family boat making its way to the morning market - were all

just another day in the life of the Mekong. There were intimate moments the

photo lens could never capture, but they would remain embedded in my mind forever.

After

a brief city tour, including the Reunification Palace, the Cho Lon Market, Notre

Dam Cathedral and the War Remnants Museum, we set off on a two-day side trip

south to the Mekong Delta, otherwise known as the rice basket of Vietnam. Navigating

Highway 1 at speeds exceeding 110 mph with our guide, Ut, we headed towards

the Delta, the floating markets and the city of Can Tho. As we set out for the

morning market on the Delta, we passed through narrow canals shaped by dilapidated

homes flushed up against the banks. The Kodak moments - a woman rinsing clothes

in the river, a family boat making its way to the morning market - were all

just another day in the life of the Mekong. There were intimate moments the

photo lens could never capture, but they would remain embedded in my mind forever.

Our wooden boat bobbed up and down through the cluster of floating markets, occasionally detouring so we could nuzzle up close to see the goods. We came upon a boat selling iced coffee, made to order. After finishing a second glass of the delightful drink, surrounded by the organized chaos and vibrancy of the Mekong, It was as if we had discovered the best place on earth. Ut enjoyed watching us relish in our surroundings. He said we did not conduct as tourists, but instead acted more like the locals. I accepted our guide's observation as a compliment and could feel the Vietnamese blood flowing through my veins.

After resting our sea legs, we took a three-hour xich lo ride along the rural countryside of Can Tho. Though just a two-seater with a canopy, Ut straddled himself behind the driver to provide a narrated tour. Our tour granted us a bird's eye view of Can Tho's rural homes lined along bustling waterways. Just like the pieces to a jigsaw puzzle, shacks leaned delicately against one another facing every which way, many beaten and tattered. From time to time we passed a schoolyard, identified by a yellow building and small bodies in uniform. Children at play would run into the unpaved road shouting "Hello!" Despite the poor, rugged and rural elements, we were greeted with smiles and nods as our xich lo made its way along the bumpy, unpaved road.

My expectations of the Mekong Delta were not met, but instead far surpassed. The beauty of the Delta, the friendliness of its people, and the simplicity of rural life would never be forgotten and now symbolize to me the heart of Vietnam. For the time being, though, we had to say farewell and make our way back to our central checkpoint in Saigon. We enjoyed another day in the city before catching our connection to my homeland just an hour's flight north, in the city of Quy Nhon. Once a bustling coastal port during the American War, Quy Nhon sits on the South China Sea in central Vietnam, between the cities of Da Nang and Nha Trang.

As we neared Quy Nhon, all the pictures I created in my mind for so many years began to take shape. The mystery of what this place held for so many years would soon unfold. As we landed, Brad tapped me on the knee and said "We made it, you're home." It was a strange feeling landing in the middle of rural fields. The bare and remote landing strip didn't resemble much of a homecoming and the sparse surroundings in no way symbolized what I knew as home.

Our bags came off the conveyer belt, a reminder to me that our backpack contained black & white photos and documents that explained what little there was to know about my brief life in Quy Nhon. A scrapbook was given to my family at adoption that contained a narrative about life in the orphanage and photos of various children, including one of me. For so many years the scrapbook remained closed, never revealing what may have preceded my life as an American. As I held the papers in my hands, more than ever I wondered what questions they might answer.

As we made our way through the makeshift airport, our new guide, a middle-aged Vietnamese man by the name of Cuong, greeted us with a warm smile. A decorated pilot who fought for the South Vietnamese in the War, Cuong flew over 600 missions, strategically dropping bombs along the Ho Chi Minh Trail. In broken English he described to us his training in the U.S., his missions over the DMZ, and the years he spent doing hard labor in a re-education camp run by the Vietcong. A guide of 7 years, it was Cuong's first tour with a Vietnamese woman.

After meeting up with our driver we were on our way to Quy Nhon, about 30km from the airport. Immediately the pictures of Quy Nhon archived in my mind all these years were transformed and brought to life. As we headed down the narrow dirt road, our driver honking relentlessly, we passed large water buffalo hauling rice, fresh vegetables and other agricultural goods. It felt like we had entered into a time warp. The silk and lacquerware shops of Saigon's Dhong Khoi Street never made it here. We traveled by vast green rice fields decorated with pointy cream-colored conical hats, a sign of farmers harvesting their latest crop.

For most travelers, Quy Nhon is not a highlight on the itinerary. It mainly serves as an overnight pit stop for tour groups making their way from north to south Vietnam. The tourists we did see never left the hotel restaurant. Two or three buses of westerners rolled up in the early evening, took the restaurant and lounge by a storm, and were gone by morning. We arrived at the hotel, pleasantly surprised by the beach and ocean view. After checking in, we were eager to get our bearings in order. We raided the hotel mini bar of a few Ba Ba Ba's (local beer) and took to the beach to explore. I've seen several beaches in my lifetime, but none of them held a candle to this one and no other would ever be remembered in quite the same way. Simply being in Quy Nhon generated more emotions than I could ever quantify.

As young Vietnamese and their motor scooters took to the streets by nightfall, we ventured out towards the city to check out the nightlife. Everything felt primitive and simple. The city felt unusually small and much more intimate than I had imagined. It was night and day from the life I led in America. Every so often, I would think about what my life could have been like and sometimes wondered if even some of these people were related to me. That night I went to bed wondering what answers Quy Nhon held, if any.

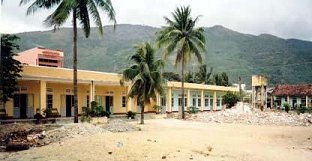

The next day we spent the morning visiting the Nguyen Nga Vocational Center. Established 10 years ago by a young Vietnamese woman, the center is dedicated to helping disabled and orphaned children. When established in 1993, the center was in the abandoned Ghenh Rang Orphanage where I was cared for in 1975. Naturally, its ties to my background sparked an immediate interest. In the months preceding our trip, we learned more about the center and our devotion led to fundraising efforts to help the overwhelming number of children in need. Our connection would later result into a warm invitation to visit the center during our trip, meet the children and tour the facilities.

Upon our arrival, we were greeted with warmth and hospitality by the staff and children. It was an incredible feeling to finally transform the bond we developed into real people and real needs. The facilities were lacking in ever way, but the children didn't seem to mind and their happiness and laughter surpassed all the physical hardships they endure daily. One after another, the children appeared, some stricken with polio, some blind and some deaf. It is believed that some of the children are handicapped as a result of their parents' exposure to Agent Orange or Napalm during the War.

The

children played music, sang songs and one young girl sketched my picture. We

sat in this building, joined by the sounds and sights of children who knew nothing

beyond their disabilities and that room, and I realized these moments would

forever change my life. As much as they wanted me to be a part of their lives,

I wanted them a part of mine. We toured the nearby building that housed the

deaf students and were amazed at the meager conditions. No beds or mattresses,

just an unfinished wooden floor with a partition separating the boys and girls.

The deaf children were loud, excited and full of life. They marveled in my ability

to interpret my name and greet them in sign language. I was only providing a

small monetary impact on the lives of these children, and little would they

know the life-long impact they would have on me. After an inspiring morning

at the center, we reluctantly said our good-byes and regrouped with our guide

and driver to begin the rest of our Quy Nhon adventure.

The

children played music, sang songs and one young girl sketched my picture. We

sat in this building, joined by the sounds and sights of children who knew nothing

beyond their disabilities and that room, and I realized these moments would

forever change my life. As much as they wanted me to be a part of their lives,

I wanted them a part of mine. We toured the nearby building that housed the

deaf students and were amazed at the meager conditions. No beds or mattresses,

just an unfinished wooden floor with a partition separating the boys and girls.

The deaf children were loud, excited and full of life. They marveled in my ability

to interpret my name and greet them in sign language. I was only providing a

small monetary impact on the lives of these children, and little would they

know the life-long impact they would have on me. After an inspiring morning

at the center, we reluctantly said our good-byes and regrouped with our guide

and driver to begin the rest of our Quy Nhon adventure.

It was tough to change paces when we returned to the car, but we quickly turned our attention to locating the site of the Ghenh Rang Orphanage. I provided Cuong with some rough directions, but there was some concern that the orphanage buildings had been recently torn down by the government. Coung was less optimistic, but we were determined to visit the site even if the orphanage had since been replaced.

We

neared a small church on a corner street and Cuong decided we should investigate.

We entered the small compound and knocked on a set of wooden doors. They quickly

flung open and an unusually tall Vietnamese man greeted us. He seemed startled

by the sight of a towering Caucasian man and Vietnamese woman. Cuong quickly

broke the silence and soon after we were escorted into a small dark room. The

priest had come to Quy Nhon in 1975, just as the War was ending and new very

little about the orphanage. He studied the photos and stated the orphanage was

just behind the church. Within minutes we were in an alley standing behind two

rusted iron gates. I took one look through the iron bars and knew this was Ghenh

Rang.

We

neared a small church on a corner street and Cuong decided we should investigate.

We entered the small compound and knocked on a set of wooden doors. They quickly

flung open and an unusually tall Vietnamese man greeted us. He seemed startled

by the sight of a towering Caucasian man and Vietnamese woman. Cuong quickly

broke the silence and soon after we were escorted into a small dark room. The

priest had come to Quy Nhon in 1975, just as the War was ending and new very

little about the orphanage. He studied the photos and stated the orphanage was

just behind the church. Within minutes we were in an alley standing behind two

rusted iron gates. I took one look through the iron bars and knew this was Ghenh

Rang.

Cuong summoned the attention of a woman who graciously unlocked the gates and let us in. With the exception of a new coat of paint, the exterior of the buildings was a mirror image of their existence in 1975. Though the palm trees had tripled in size, the lush and hilly backdrop remained unchanged. It was amazing the buildings were still in tact, as piles of brick and other debris surrounded them. We took several pictures and stood there in silence. Visiting the site gave a small degree of satisfaction, but the events that transpired in 1975 would remain a mystery. We would soon learn that after the center's disabled and orphaned children occupied these buildings in 1993, they were eventually overtaken by the government and are now being used to house the elderly.

Eventually we shut the old rusted gates behind us and left the orphanage site. It was a small triumph, but it was the one goal we traveled all this way to fulfill. Satisfied with our findings, we made our way back to the priest and the church. We sat patiently as Cuong translated my adoption papers. By this point, we werent sure what information, if any, he was trying to obtain. After a brief disappearance, the priest reappeared with a small yellow book. Cuong explained that the priest knew of the woman mentioned in the documents and that she was living in Quy Nhon. Overwhelmed with shock, I watched as Cuong jotted down her address and telephone number.

It was not uncommon for many orphanages to be run by Catholic nuns during the War and the Ghenh Rang Orphanage was no exception. In fact, had it not been for one very special nun, Sister Emilienne, I never would have been part of the airlift out of Saigon. I had come to know Sister Emilienne only through documents provided by the adoption agency. An affidavit described her brave efforts during the War and her involvement in escorting children to Saigon for safe evacuation to the U.S. as the Vietcong moved in.

The odds that we would meet her were slim and before coming to Vietnam I never even entertained the idea of even looking for her. I just assumed she was either dead or had left Quy Nhon years ago. Cuong dialed her number from his cell phone but there was no answer. Our sudden hopes were quickly deflated and we assumed that the meeting would not take place. We were ushered to the car and headed down the streets of Quy Nhon. Our driver made a couple of stops at street vendors and Cuong asked several questions in Vietnamese. We weren't entirely sure what was going on. We would jump out of the car, only to quickly jump back in the car and be off again down the busy streets of Quy Nhon. We eventually pulled into a narrow alley and the car pulled up to a set of large iron gates. Cuong asked us to get out of the car and a couple of young women politely greeted us.

Cuong exchanged a few words in Vietnamese and everything after that happened so quickly. As we were invited in, Cuong explained that this was the convent where Sister Emilienne lived. Within seconds a petite Vietnamese woman appeared and Cuong looked to me and said "Nguyen Thi Thanh Truc," my Vietnamese name. Sister Emilienne hugged me without hesitation, nearly crying "I've wondered all these years what happened to you and if you would ever come looking for me." The idea that this woman had thought of me all these years, never forgetting who I was, was beyond disbelief. I was overwhelmed with emotions that all the years behind me could never prepare me for.

I

felt numb head to toe and I couldn't conger up a reaction to match Sister Emilienne's.

The memories of 1975 came back to her like it was yesterday. I, on the other

hand, was an infant then and had no memory of her or this place. I wanted so

badly to connect in the same way. She recognized me without question and said

she remembered all the details of my infancy. After several hugs, laughs and

a few tears, we finally sat down. She kept her arm linked to mine and smiled

with joy. I couldn't believe I was sitting with the woman who cared for me and

was responsible for my evacuation from Vietnam. I learned that I came to the

orphanage from the local hospital, with my umbilical cord still attached. Sister

Emilienne was told my mother was very ill following my birth and knew nothing

more about my birth parents. She took me in at the orphanage, cut my umbilical

cord and gave me my Vietnamese family name, Nguyen - the same as hers. She told

me she considered me her own, like a goddaughter, and my husband her son-in-law.

I

felt numb head to toe and I couldn't conger up a reaction to match Sister Emilienne's.

The memories of 1975 came back to her like it was yesterday. I, on the other

hand, was an infant then and had no memory of her or this place. I wanted so

badly to connect in the same way. She recognized me without question and said

she remembered all the details of my infancy. After several hugs, laughs and

a few tears, we finally sat down. She kept her arm linked to mine and smiled

with joy. I couldn't believe I was sitting with the woman who cared for me and

was responsible for my evacuation from Vietnam. I learned that I came to the

orphanage from the local hospital, with my umbilical cord still attached. Sister

Emilienne was told my mother was very ill following my birth and knew nothing

more about my birth parents. She took me in at the orphanage, cut my umbilical

cord and gave me my Vietnamese family name, Nguyen - the same as hers. She told

me she considered me her own, like a goddaughter, and my husband her son-in-law.

We spent time looking at photo albums and sharing as much as we could about one another. She explained to us that since 1975, four or five other children from the Ghenh Rang Orphanage have returned to meet her as well. She wondered all these years why I hadn't come back and she worried that maybe I never would. My only defense was that I didn't know where she was or how to find her. I couldn't explain that it took this long for me to reconcile my feelings about Vietnam. Eventually, after condensing several years into mere hours, it was time for us to say good-bye. It was hard to imagine that so much time had passed, that my life had endured so much change, and yet this woman had preserved her memories and her entire life in this intimate place. I tried to imagine what it was like to have someone invade your life and recreate experiences very few have lived. Despite the memories of a painful war and a culture so different, Sister Emilienne greeted me into her life without reservation. She is a wonderful, kind woman and like the rest of Vietnam, she has left a permanent imprint on my life.

Before ending our reunion, Sister Emilienne asked if I could come and live in Vietnam with her. She offered the convent as a home and said she could help me find a job. When asked about my husband, she said he could just return to America. We all laughed at the thought, but deep down I sensed her invitation had no expiration. We exchanged e-mail addresses, promised to write and she asked for photos from my childhood. After so many years of separation, I wanted to believe I could bridge the gap between our lives and our cultures. As we drove away, sadness took hold, knowing it would be a long time before I would return, if ever again.

Leaving Quy Nhon the next day was bittersweet. I gained so much more than expected and knew I would return home a better person because of it. Yet I couldn't help but feel that I was leaving so much behind, a part of my history that might never integrate into my real life. I didn't know how I would balance the two, but was willing to try. Before returning to the states, we made a final stop in Nha Trang, about a 4-hour drive south along the treacherous Highway 1. Nha Trang's coastal beach was lovely and it was just the spot to decompress from the whirlwind of events in Quy Nhon. Though still a part of this beautiful country, it already felt like light-years away from Sister Emilienne and all else that had transpired. Nha Trang, just like the rest of Vietnam, helped transcend years of misconception into a new and better understanding of my heritage.

Days

later we returned to Saigon and prepared for our final departure from Vietnam.

I knew these experiences would forever change my life, but I wasn't sure until

now how the journey as a whole would affect me. I am more confident than ever

to be Vietnamese and hope to represent Vietnamese culture proudly. It may be

years before I ever return, but I feel like a piece of me remains in Vietnam.

Nearly 30 years ago I was adopted into America, and now I have in turn adopted

Vietnam. It is an experience I intend to transcend into my life, my relationships,

and someday my children.

Days

later we returned to Saigon and prepared for our final departure from Vietnam.

I knew these experiences would forever change my life, but I wasn't sure until

now how the journey as a whole would affect me. I am more confident than ever

to be Vietnamese and hope to represent Vietnamese culture proudly. It may be

years before I ever return, but I feel like a piece of me remains in Vietnam.

Nearly 30 years ago I was adopted into America, and now I have in turn adopted

Vietnam. It is an experience I intend to transcend into my life, my relationships,

and someday my children.

I have discovered a new refuge in Vietnam and the connection I feel gives me an identity no other experience could ever give. I went to Vietnam to close a chapter in my life, never realizing a new one would begin. I do not know what my future with Vietnam holds, but I do know that this experience has allowed me to embrace simultaneously that I am an American, that I am adopted, and most importantly, that I am Vietnamese. As our plane turned away from Saigon and began its ascent, I knew I had transformed during this two-week journey. In April of 1975 I evacuated Saigon and would spend years closing the door on the country that today allows me to identify who I am. Now, as we made our departure, more than ever I wanted to stay. In that brief moment I realized nearly 30 years after my rescue I was again flying over Saigon and that my life was about to forever change.